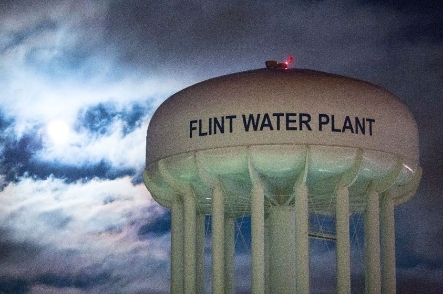

Attorney General Bill Schuette said at a news conference in Flint that the civil lawsuit was filed in Genesee County Circuit Court against Veolia Environnement SA and Houston-based engineering services firm Lockwood, Andrews & Newnam (LAN).

The lawsuit charged Veolia with professional negligence and fraud that caused Flint's the lead poisoning to continue and worsen, and LAN with professional negligence.

Schuette said the state is seeking damages from the companies that could total hundreds of millions of dollars. His office said additional claims against the firms or others may be filed in the future.

"Many things went tragically wrong in Flint, and both criminal conduct and civil conduct caused harm to the families of Flint and to the taxpayers of Michigan," Schuette said. "In Flint, Veolia and LAN were hired to do a job and failed miserably, basically botched it. They didn't stop the water in Flint from being poisoned. They made it worse."

Veolia was hired in February 2015 by the city to address drinking water quality and produced at least one report and one public presentation stating the city's water was safe to drink, according to the lawsuit. The company knew its representations were false, the lawsuit stated.

Paris-based Veolia said Schuette's office did not contact the company about its work and that its contract was unrelated to the current lead problem.

It said it will defend itself against "these unwarranted allegations of wrongdoing." Veolia shares dipped 0.2 percent.

In 2013, LAN worked with Flint to prepare the city's water plant to treat new sources of drinking water, including the Flint River, according to the lawsuit.

LAN did not issue corrosion control measures in April 2014 and in August 2015 produced a report saying the water met federal safety requirements, failing to recognize the lead problem, according to the lawsuit.

In a statement, LAN said it "was not hired to operate the water plant and had no responsibility for water quality." It will "vigorously defend itself against these unfounded claims," it said.

Flint, with a population of about 100,000, was under control of a state-appointed emergency manager in 2014 when it switched its water source from Detroit's municipal system to the Flint River to save money. The city switched back in October.

The river water was more corrosive than the Detroit system's and caused more lead to leach from its aging pipes. Lead can be toxic, and children are especially vulnerable. The crisis has prompted lawsuits by parents who say their children have shown dangerously high levels of lead in their blood.

Last month, a Flint utilities administrator agreed to cooperate in investigations as part of a deal with prosecutors. Two state employees have been charged by Schuette's office, and he reaffirmed Wednesday that other employees would be charged as the investigation continues.

Todd Flood, who is leading the state probe, said on Wednesday he has not received all documents that have been requested, including those from Gov. Rick Snyder's office. Some people have criticized the governor and called on him to resign for the state's poor handling of the crisis.

When asked if Snyder was a target in the investigation, Schuette said there are no targets but "nobody is off the table."

In 2013, the administration of St. Louis Mayor Francis Slay pushed to sign a $250,000 consulting contract with Veolia, saying that the company would help make the city water division more efficient. But the proposal met with strong opposition, and Veolia withdrew from consideration.

Original article; St Louis Post Dispatch, June 22, 2016