by Fintan O'Toole

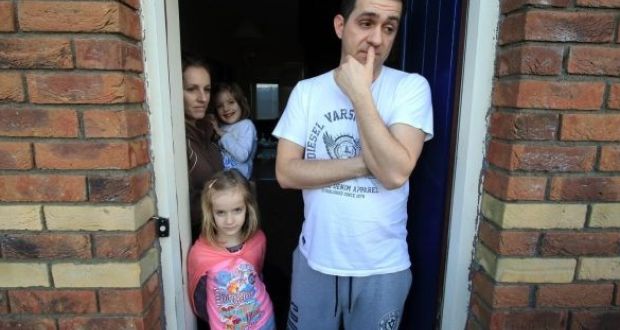

Martin Maloinowsk is among the familes facing notice to quit their homes in Tyrrelstown. Photograph: Nick Bradshaw/PA

One of the easiest things to remember when you study Irish history is the programme of the Tenant Right League, established in 1850. It campaigned for the Three Fs: fair rent, free sale and fixity of tenure. The eventual winning of those demands was a huge part of the emergence of modern Irish democracy: the underlings becoming a political force that had to be reckoned with. And now, 166 years later, we have the Three Fs again. As the people of Tyrrelstown know only too well, the new Three Fs are two fingers and a “feck off outta here”.

Or as Rick Larkin, the property developer at the centre of the Tyrrelstown evictions, put it in the Sunday Business Post: “As a tenant your accommodation is a temporary arrangement. It is not permanent because you don’t own the home and you don’t have security of tenure.”

These exact words could have been spoken by a titled landlord in 1850.

We have a weirdly contradictory relationship to our history. On the one hand it stirs us and moves us. The commemorations of the 1916 Rising have real force for most of us. Beyond the crassness and the flag-waving, there is a genuine desire for a connection to a common past, a shared inheritance of struggle for collective dignity. That is a fine thing.

Yet on the other hand this sense of history is curiously abstracted. It is cut off from any real notion of what’s actually happening in the place we inhabit.

The point of the shared inheritance of struggle should be that it makes us feel empowered. Instead, it tends merely to make up for our lack of power. The pride we take in the past seems only to compensate in some strange way for the shame of our current condition.

We are masters of irony, though some of it is so heavy-handed that it would get you thrown out of a creative writing class. Consider Boland’s Mills, one of the main sites of the Rising. It is a resonant place in the history of the State because it was his command at Boland’s Mills (and the luck of being the only such commander to survive) that gave Eamon de Valera his mythic authority as apostolic successor to Patrick Pearse.

Do you know what’s happening to Boland’s Mills now? It is being rebranded. Boland’s Mills is becoming Boland’s Quay. Nama is using €170 million of public money to develop, through the giant British property company Savills, an enormous scheme for 30,000sq m of office space, with some high-end apartments and shops. Planning process This is the biggest construction project in the city in the last decade. It was rushed through the planning process in less than a year under the fast-track strategic development zone process. And this scheme is in turn part of Nama’s €7.5 billion development programme for 20,000 new homes and four million square feet of commercial space in Dublin’s docklands.

Dublin has not seen a government-driven development scheme on this scale since the 18th century.

Apart from the symbolism of turning the historically laden Boland’s Mills into the history-free Boland’s Quay, this tells us about two big things.

One is the sense of priorities. Here we have the State mobilising vast resources to develop commercial offices and homes for the private market. Yet this same State is unable to stop communities like Tyrrelstown from being torn apart by the rules of that same market. And it’s unable to act as a developer of public and social housing. The power of the State is skewed away from the needs of citizens and towards market needs.

The other thing that is happening here is the absence of democracy.

Aosdána, the official body of artists, has accurately described the Nama plan as “one of the most significant actions ever proposed for the city of Dublin by the government”. It is being done by a public agency on behalf of the citizens. Yet those citizens are locked out of the process. Social needs None of us gets a say either on the principles of the State prioritising private commercial development over social needs or on the actual plans.

They may be on the same site but it’s a hell of a long way from Boland’s Mills to Boland’s Quay.

For all their failings, the rebels believed the point of a republic was to shift power from remote authorities to Irish citizens acting collectively. How’s that working out for us? Are tenants any more secure now than when they were subject to the whims of ascendancy landlords? Is Nama more answerable to Irish democracy than Whitehall mandarins were in 1916?

Next week we’ll be waving our Tricolours with pride. But we should not let them be used as fig leaves to cover the shame of our lack of collective power and the nakedness of our democracy. We need not just to celebrate our own history but to live it.

Original article: Irish Times, March 22, 2016

Read full story; RTE March 14, Tyrrelstown tenants meeting over eviction notices