Last month I saw a picture, a photograph, that burned down the Potemkin village of American politics that tends to rise in even the most skeptical mind during the fever dream known as the presidential campaign. We all get caught up in it, especially those of us who’ve been following politics for decades, and were marinated for many years in a mainstream perspective. I myself was raised as a “yellow dawg” Democrat in the South. The idea, of course, was that no matter whom the Democrats nominated—even it was a yellow dog—you voted for them. My father—perhaps to his credit?— carried on with this ideal long after almost all of his fellow white rural Southerners had abandoned the Democrats for the dog-whistle racism of the modern Republican Party. I remember well one of his most abiding pieces of political wisdom. It was 1984, and a neighbor of ours—a big, hulking, slightly backward country boy who’d been devoted to my father since their school days—told him: “Chief, I’m thinkin’ about votin’ for Reagan this time. What do you think?” My father leaned against the back of his pickup truck and said in a cool, even tone: “Buford, a man who’d vote for Reagan would eat shit.” Buford nodded his head vigorously. “You right about that, Chief!” (But I’m sure he voted for Reagan anyway.)

Hillary Clinton, Ted Cruz, Berni Sanders and Donald Trump

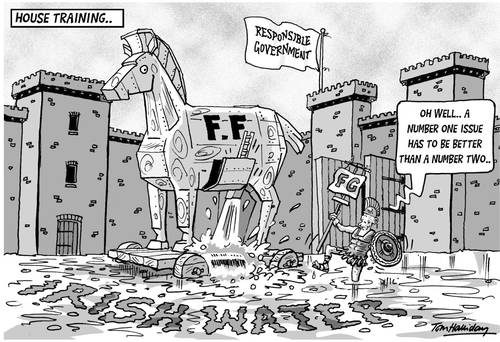

So I’m well aware that it’s hard not to get caught up in the horse race of the Grand Quadrennial Derby: “Was this a good move for Bernie? Will HRC take a hit from Bill’s gaffe? Is Trump faltering? Will the GOP elites come around to Cruz?” And so and so forth, with the myriad other permutations and speculations that can dazzle the mind—and numb the moral sense—while watching the political circus.

But then something will shake you— or slap you—awake. And so one day I saw a photograph someone tweeted from the Yemen Post. It showed a young girl—12, 14, the age was hard to tell. She was on her hands and knees face down in the dirt, trying to suck water from a hole in a dirty rubber pipe. And in that instant, all the silly, stupid, evil folderol of the campaign circus, all the earnest bunting that adorns the Potemkin village, fell away. I saw the picture, and I knew—once again—this is America in the modern world. This is American foreign policy. This is what it is, this is what it does. This is a war that our Peace Prize-winning president has been conducting with his Saudi allies for more than a year. It’s been responsible for the “excess deaths” of 10,000 children, according to UNICEF. (Let’s repeat that: TEN THOUSAND CHILDREN.) It has driven millions to the brink of famine. It has destroyed schools, hospitals, infrastructure. It has been a gigantic boon for al Qaeda by attacking its deadliest foes in Yemen, the Houthis, and giving it scope to spread.

It is a humanitarian disaster and a moral outrage of the highest order. And yet ... there is no outrage. There is scarcely any notice, beyond a bare minimum of “marginal” websites and a few stories deeply buried, and stripped of context, in the bowels of the mainstream press. In the past year, a “progressive” administration—whose policies will be continued by either of the Democratic nominees (yes, even Bernie says he wants to see more Saudi militarism in the region)—has been directly complicit in the deaths of TEN THOUSAND CHILDREN. And no one involved in the presidential circus—not the candidates, not the media, not the analysts, not the horse race afficianados—gives the slightest damn. None of them—and nothing in the sinister clownery of his election—deals with the reality of what we are doing in the world. No one will speak of its true, deeply criminal nature—not even the “radical,” “revolutionary” “Democratic Socialist” candidate. So what, in the end, are they really talking about? They’re talking about nothing. They’re talking about bullshit. They’re talking about anything on God’s green earth—or rather, God’s bloodstained, gouged-out, dying earth—but reality.

The reality is a young girl forced to go down on her hands and knees to pry a few drops of water from a broken pipe. She could be your daughter. She could be you. She is a human being who did nothing wrong but be born in a place where a few “progressive” American elites—headed by the Peace Prize-winning president—wanted to play with their head-chopping, womanhating allies to achieve and maintain dominance over the oil lands and their strategic environs. In the end, it comes down to that brief scene in Warren Beatty’s film, “Reds,” where a plump, patriotic bergmeister from Portland calls on Jack Reed to explain “just what this war [WWI] is all about!” Reed rises amongst the tuxedoes and pretty outfits at the gathering and says but a single word: “Profits.” That’s why the Yemeni girl is face down in the dirt, scrambling desperately for water. That’s all it’s about, this “war on terror,” that’s the only thing it’s ever been about: profits. And whoever is elected, that’s not going to change.

Original article: http://www.counterpunch.org/ Vol 23 no 2 Apr 2016